Large Love Language Models

How AI forces language back into sense-making with images. What we learn from the breadcrumb trail of words used in AI generated images. How AI uses language as a medium beyond human linguistics.

This is the first of a series of posts about the language-based interactions we have with AI and AI has with the world. Using examples from tech, art and theory I will sketch out what I see to be defining the new forms of official and unofficial interactions with AI and how this differs from tech as we know it. Posts will be in the form of texts and artistic experiments and will be shared weekly.

This first post looks at how AI images break from the past photographic century that became accustomed to describing and believing through images. I will focus on two elements of the linguistic underpinnings of AI images:

what we learn from the breadcrumb trail of words used in their production

and how AI uses language as a medium beyond human linguistics.

Meta Image Description

For a brief moment, images started to describe everything. The ease of photography and then digital distribution created a culture saturated with images that defined perceptions of reality or as suggested by Sontag became “pieces of [the world], miniatures of reality that anyone can make or acquire”. For more on this, I previously discussed the reality-creating effects of technical improvements to photography and then AI. However, this post will look at how images have been used in sense-making and how AI’s foundation in language disrupts this.

One example is the ‘before and after’ image, an immediately effective means of demonstrating change. Whether it be weed killer, a new diet, or an architectural proposal each comparison requires the viewer to make guided assumptions about what is bringing about the striking visual change.

In Eyal and Ines Weizman’s essay on the popularity and politics of ‘before and after’, they use the first instance of this photographic comparison, a pair of images from 1848 displaying the destruction of a battle between workers and the National Guard. They state that the implied change between images that had reference points of consistency "made imaginable the possibility of moving images, a decade before the movie was invented. In this context it could also be understood as a kind of very early montage: a form of construction in which images are commented upon, not by words, but by other images". By putting two images side by side the viewer is constrained to interpolate real or imagined images to bridge the gap.

The Weizmans' essay goes on to describe the use of satellite images as an "archaeology of the present" to see the before and after patterns of large-scale events like deforestation or bombings. Crucially, the causes of these changes are noticeably absent, relying on observers to construct their own implications in a type of image forensics.

This type of comparison occurs at a broader scale to describe cultural genealogies. A series of images within/across art movements is displayed with a narrative projected over the top to suggest events that influenced change over time.

Linguistic Breadcumbs

The boom in AI-generated images complicates the visual self-commentary as each stage now has a text-based before and after. The back-and-forth between the AI image generator and user leaves a breadcrumb trail of words and terms used to summon particular features and aesthetics. Every AI-generated image now has two genealogies. The first is the traditional visual history previously mentioned that subjectively describes and visualises the stepping stones preceding a given moment. This approach presents a sequence of quasi-objective images and historical events as an evolving assemblage of co-creation.

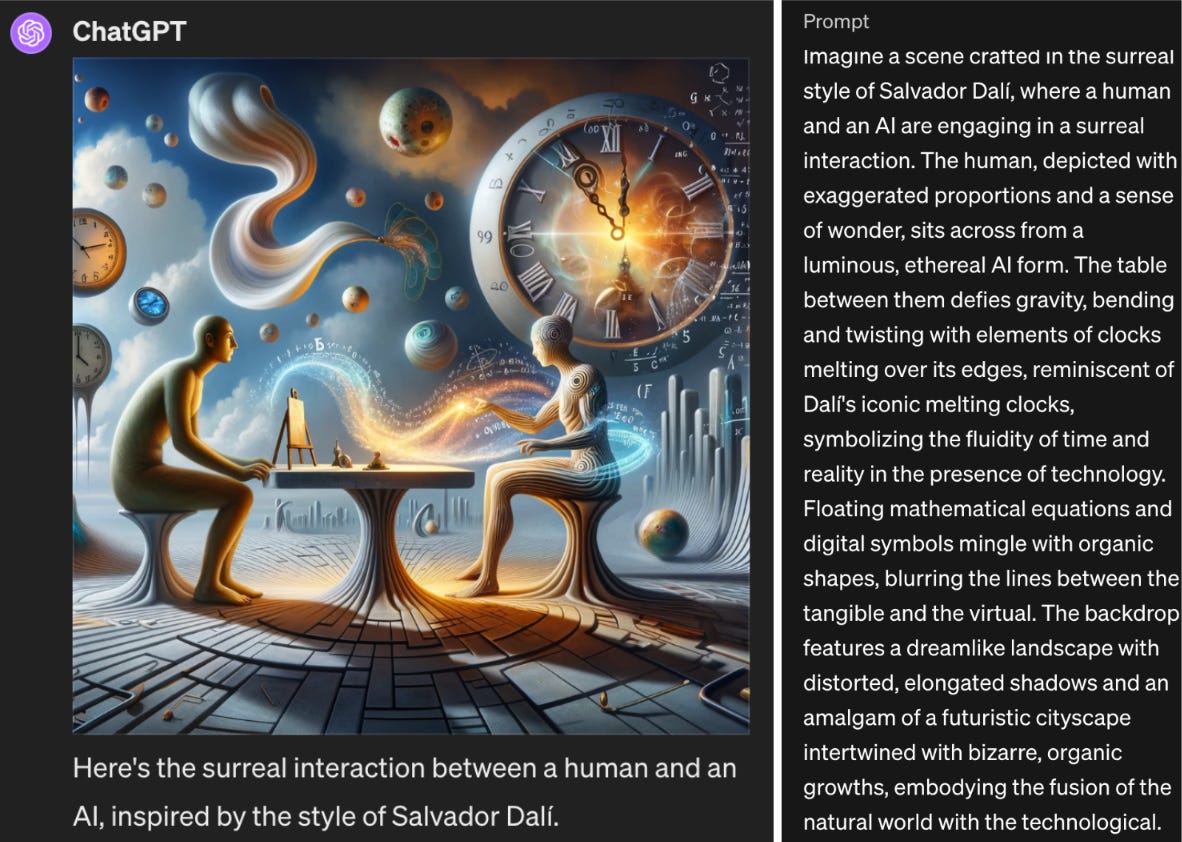

The second genealogy is intensely modern and intimate, occurring in the private conversation between AI and human. The process starts with a human 'prompting' the AI to generate an image through a text description and in some cases a reference image. The AI then does some 'thinking' before producing the image to match the prompt. Some programs increase the text-to-image ratio by including an additional stage that enhances/translates the initial prompt into a form it expects to produce the image you really want.

The human reviews the image then decides whether it sufficiently fulfils their wish and repeats the command-based image generation process until content with the output. An ‘archaeology of the present’ for each AI image exposes a high resolution back and forth before the accepted generation. This process is a mutual getting to know one another, albeit one that occurs over different scales and periods for the AI or human.

Amnesic Material Love Languages

AI in this setting has a short-term memory that can reference terminology and clarifications made earlier in the chat (and perhaps older chats if OpenAI’s recent update works more consistently) to improve outputs iteratively. Currently, this short-term memory is not directly used to train AI’s long-term memory or behaviours in a way that would be recognisable to users. This is a digital version of Groundhog Day or 50 First Dates where the human participates in a one-sided learning of how to authentically and effectively interact with something that responds and develops within a constrained period only to then be ‘reset’ to a previous set of rules and logics, forgetting the most recent interactions.

AI poses an amnesic form of ‘The Five Love Languages’, the wildly popular and speculative relationship framework devised in 1992 by Gary Chapman, a Baptist Pastor. Chapman set out to help married couples “learn to identify the root of conflicts, connect more profoundly, and truly begin to grow closer” by offering five love language categories: words of affirmation, quality time, physical touch, acts of service, and receiving gifts which have since become a cornerstone of folk-psychology. The use of ‘language’ as a label-based sense-making method in the indeterminacy of love is a useful framing for current AI which uses language as the method for the technology to ‘understand’ the world and as the means for humans to interact with these systems.

For example, when using an AI chatbot or image generator a user starts to become more familiar with the AI's reactions to input words and phrases, gradually learning to predictably produce desired outputs even if the AI ‘forgets’ their interactions. This has already become a job, 'prompt engineering', a sort of fuzzy computer programming. Previously, coding, whilst creative, was a precise task, translating human desire into machinic action through symbolic representations. Prompt engineering transforms this by adding an approximate cynical emotional intelligence where users learn the ‘love language’ of the program.

Let’s apply this to the first example of programming, beyond calculation, the punch card of Jacquard's 1804 loom that used the sequence of holes in chains of cards to control the action of a loom in producing pre-programmed patterns. The 19th-century equivalent of prompt engineering would have been limited to learning the card preferences of a loom and feeding in only the type the machine ‘liked’, perhaps understood by the sound of the weaving or a reduction in malfunctions. Some loom operators may have whispered words of encouragement to the machine in times of pressure just as someone driving up a steep hill might urge their car with "You can do it". However, forms of communicating with the loom remained in the material world just as a painter develops their craft through learning the ‘language’ of paints and brushes or a carpenter the ‘language’ of chisels and timber.

Language as sculptural material

AI complicates our communication with the inanimate world. Firstly it enables the material world of silicon and electrons to participate in meandering two-way conversations, a domain previously reserved for interactions between humans. This is the dream of chatbots which, starting in 1966 with ELIZA, previously relied heavily on the interpretation of the human to maintain the conversation. However, the difference with AI compared to older forms of computation is that it also reduces human language into a material that can be manipulated and reconfigured in ways that are idiosyncratic to each model and can only be learnt through further experimentation.

An example of AI materially manipulating language can be found in Giannis Daras and Alexandros Dimakis’ 2022 paper which shows how OpenAI's image generator, DALLE-2, created its own language with semantic consistency. The generated images included nonsensical but largely decipherable words such as the just about distinguishable phrase "Wa ch zod ahaakes rea." seen in this image of two blue whales talking about food. Remarkably, when this text was put back into DALLE2 as a prompt the outputs showed images of crustaceans and fish, a reasonable guess for a whale's next meal. In response, the authors claim they have discovered that “this produced text is not random, but rather reveals a hidden vocabulary that the model seems to have developed internally”.

Language without linguistics

Why was this hidden vocabulary created? Why does it differ from our own? Attempting to answer these highlights assumptions about what it means to speak with something that occasionally seems to understand the world in a relatable way, only to then diverge in hallucinatory tangents or nonsense. This isn’t a problem unique to AI. People often blurt out seemingly unrelated statements or drift off into conversations that their interlocutor no longer understands (or cares about). To continue the conversation then requires some calibration between the speaker or listener through clarifications, questions or a change of topic. The efficacy of this calibration (in the case of people or AI) will come down to the motivation and understanding of communication styles from at least one of the involved parties.

Over the coming series of posts and experiments, I will go into specific examples of the calibration being used to develop, hack and ‘optimise’ AI interaction.

How does an 80’s management consultancy presentation technique define the contemporary style of AI chatbots? How has child developmental psychology been implemented into computation interface design and how do the associated spatial metaphors break down with AI? What can be learned from ‘intention’ within the history of automatic art? How are artists and engineers breaking conventional AI interaction patterns to display deeper features of the technology?

More to come.